A Space Shuttle re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere in the videogame Kerbal Space Program. | Credit: Thomas Marsh

It may come as no surprise to many of the readers here that I am a big, big fan of the videogame Kerbal Space Program. A recent mod release by the name of Firefly has captured my attention as it overhauls the default, admittedly dated re-entry heating effects; it does a great job of creating something more pleasing on the eyes. Indeed, Kerbal Space Program is the reason I am into all this space stuff in the first place.

Testing the ways my designs react with the new effects in-game has made me once again engage with the entire process of bringing a spacecraft back to Earth. While many players are happy to dive into the atmosphere and land their craft wherever they please, I find a great deal of satisfaction from landing my spacecraft back on the runway, or at a designated splashdown site.

Rather unsurprisingly, there is a lot more to bringing back a spacecraft than simply letting it fall. Returning to Earth is an exercise in precision.

The Early Days

A Vostok capsule after landing. \ Credit: ESA

The desire for accuracy and control during a re-entry and landing is something that dates back to the very first spaceflight. Yuri Gagarin’s entire first (and only) foray into space was entirely automated, meaning that the spacecraft (named Vostok) would re-enter and touch down according to the pre-programmed flight profile. Naturally, the Soviet Union did not want other countries having access to their manned spaceflight technology, so the mission was to bring him back to Russian soil.

While the Vostok capsule could make corrections based on telemetry fed to it from the ground, communication with the spacecraft was patchy, and so engineers could only plan a landing to occur in a wide area of land. Gagarin eventually landed near a Kolkhoz (collective farm), and famously approached an understandably confused and frightened woman, telling them:

“Don’t be afraid, I am a Soviet citizen like you, who has descended from space and I must find a telephone to call Moscow!”

Vostok had no means of controlling its descent during re-entry, and the g-forces experienced by Gagarin reached upwards of 8 g. Simply letting the spacecraft fall back to Earth with no means of control is called a ballistic re-entry. In America, the Mercury capsules also employed this technique.

High g-forces, as well as a need for greater control over eventual landing zones, led to developments in how spacecraft are flown during this critical phase.

Controlling Capsules

Aerodynamic re-entry does what it says on the tin. This method of re-entry utilises aerodynamic effects in order to achieve some level of control over a spacecraft.

During the space race, the Apollo program needed a way to safely return astronauts from the Moon back to Earth. A ballistic re-entry would not be suitable for this task due to the higher speeds that the spacecraft would be going, as a result of returning from the Moon. Much higher g-forces and higher re-entry heating meant that the spacecraft needed to fly in a precise entry corridor. Something better was needed, but the program still planned to use the same space capsule concept from Mercury and Gemini.

It was eventually determined that by shifting the centre of mass of the capsule, the angle at which it re-enters can be altered, generating lift. By spinning the capsule around the direction of travel, this lift can be used to steer it through the atmosphere and control the speed of descent. Lower g-forces and a more precise landing zone are therefore achieved with this method.

A diagram showing 3 different angles of attack for a space capsule. The middle configuration is a ballistic re-entry, whereas the left and right configurations show how lift is generated to increase or decrease descent speed. | Credit: Farhan Lafta Rashid

This technique was used to great effect in the Apollo era, and has become the norm for any space capsule concept. Spacecraft today such as the Soyuz, Dragon and Starliner can all land within a few miles of a landing zone thanks to the control that this form of re-entry gives them.

Just Add Wings!

While aerodynamic re-entry works well enough for these capsules, they are limited by their form. A capsule can only really utilise the lift it generates during the hypersonic phase of re-entry. Once a majority of the entry is complete, and the capsule is travelling much more slowly, less lift can be generated. As noted, the landing zones for these capsules are a few square miles, and being more precise than that needed something different.

If you’re NASA, and your post Apollo spacecraft needs to be re-usable, then returning it to a precise location on Earth where it can be quickly accessed for repair and refurbishment is critical. An area of a few miles is no longer accurate enough. Something like a long, thin strip of flat land for landing might be good.

Oh yeah, those are called runways.

The Space Shuttle needed landing precision that was unrivalled by the capsules of the past. A new type of spacecraft design was needed to accomplish this feat, and the space plane was the obvious option to many.

With a space plane design, a more precise landing can be achieved. A space plane has more control over its descent in the slower portion of the entry, where a typical capsule loses much of the lift it can generate. Put simply, a space plane can re-enter like a capsule, and transition into flying like a plane once sufficiently slowed.

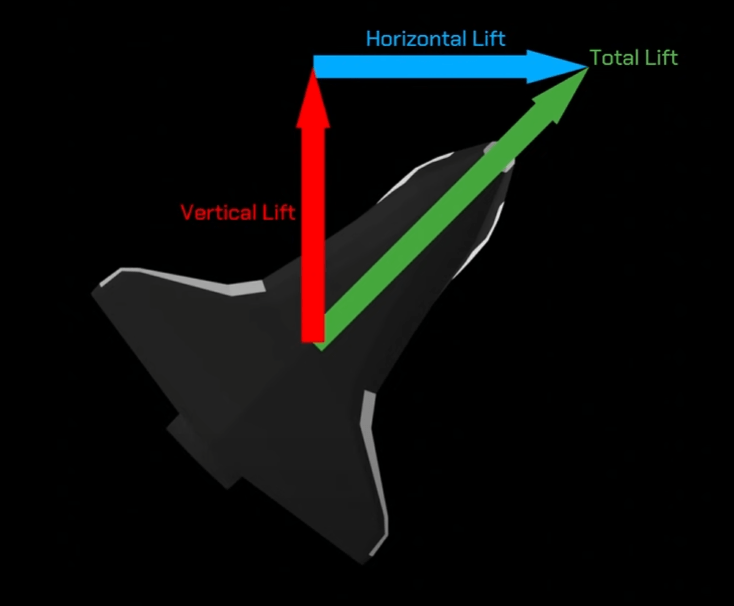

During the re-entry, the Space Shuttle, much like the capsules that came before it, held a specific angle, and rotated around its direction of travel to control the lift and drag on the vehicle. This was called the bank angle.

A diagram showing how the bank angle of the shuttle changes the direction of lift applied to the vehicle. | Credit: Simply Space

As the Shuttle had a much larger surface area than capsules, and was designed to generate more lift, it was capable of steering itself much further through the atmosphere than any spacecraft before.

As much more lift was generated, the Shuttle would change bank angle as it would otherwise skip off the atmosphere rather than fall into it. This would mean that the Shuttle would travel much further than needed, missing the target landing zone.

As a result, the Shuttle would have to reverse its bank angle every so often to maintain the correct direction. This series of manoeuvres were called roll reversals.

The trajectory of the Space Shuttle during a re-entry. Note how the direction of travel changes due to the Shuttle changing its bank angle. | Credit: NASA

The Shuttle successfully performed this type of re-entry for 30 years, landing at one of the 3 designated runways that were suitable for landing. While this precision was a level above space capsules, the Shuttle still had to be rolled off the runway, and in cases where it didn’t land at Florida, hoisted onto the back of a plane and returned to the facility where it could be refurbished for the next flight.

On top of this, giving a spacecraft all the bells and whistles of a plane is expensive when it comes to mass. Wings, flaps and landing gear adds a lot of weight that could instead be used as additional payload capacity.

The Next Generation

What if you could return a spacecraft back to the very launchpad it came from, refuel it, and go again? What if it had smaller control surfaces and no landing gear so that it could carry more payload into space?

This is the ambitious goal of SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft. The concept of Starship can be thought of as a mix between a capsule and a space plane.

The Starship utilises 4 smaller flaps on each corner of the craft to control its descent, much like a skydiver uses his/her arms and legs to control their fall. Once over the target area, the spacecraft retracts the lower flaps, ignites the engines and performs a flip in order to slow itself down using engine power for the final landing.

IFT6 test flight of Starship’s flip and landing. | Credit: SpaceX

Thus far, SpaceX has managed to return Starship to a precise spot in the Indian Ocean from space in a series of tests, but they plan to eventually “catch” the spacecraft with their launch tower. This allows them immediate access to the spacecraft so that any potential repairs and refurbishments can be made; it can also be refuelled and stacked up for another flight. Another benefit is allowing the spacecraft to fly without heavy landing gear, as all the necessary hardware to dampen the landing can instead be loaded onto the tower.

While this seems like a Sci-Fi fantasy pipedream, SpaceX has already demonstrated the concept of “catching” a booster from the edge of space during their series of integrated flight tests. The main challenge will be making sure Starship can safely and reliably re-enter the atmosphere over populated areas without breaking up, and achieving the level of accuracy needed to land back at the tower from orbit.

SpaceX Super Heavy booster being caught by the launch tower during IFT 7. | Credit: SpaceX

While they plan to test this capability this year, only time will tell how successful this concept ends up being. Personally, I’d love to see it work.

Welcome Home

I hope this little look at the evolution of returning to Earth has expanded your understanding of how spacecraft fly. Nothing is quite like coming back home, even if you’ve spent time in space.

See you next week!

Leave a comment