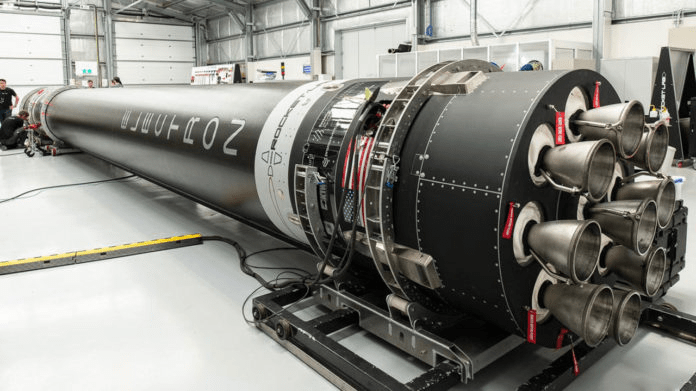

An Electron Rocket. | Credit: Rocket Lab

Bigger isn’t Always Better

Rocketry is in an interesting place at the moment. While SpaceX, NASA and Blue Origin have their sights set on larger and more powerful rockets (Starship, Artemis & New Glenn), there is also, simultaneously, a revolution of the small. Aerospace companies like Firefly Aerospace and Rocket Lab have began to compete in a market where small satellite manufacturers want specific, personalised launch parameters.

While there are a few options to choose from in the small-lift launch vehicle family, none is more iconic than the Electron, at least to me.

Today we’re going to have a look at what makes the Electron so different from other vehicles of its class, and why Rocket Lab are currently the go-to launch providers for smallsat companies.

Carbon, Carbon, Everywhere…

Much of the success of the Electron can be attributed to Rocket Lab’s willingness to utilise more modern manufacturing techniques and materials.

Building a small-sat launcher is largely about shedding weight. While this is true for all rockets, small-sat launchers must consider this to a greater extent. Many changes made to larger rockets represent a smaller percentage of overall mass, whereas even the smallest design changes can dramatically alter the overall mass of a small-lift launch vehicle.

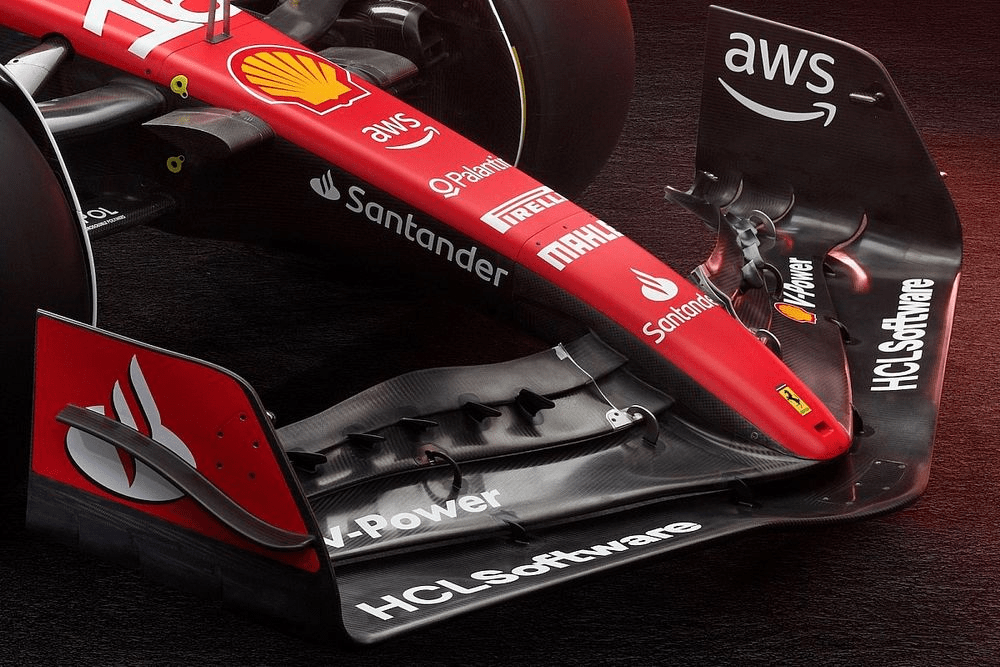

With this in mind, Rocket Lab decided to opt for a carbon composite body, something rarely seen in the rocket industry. Carbon composites are extremely lightweight but tough materials that can withstand a great deal of force compared to their overall mass. This makes them ideal for applications where being lightweight and strong is a necessity, such as aircraft, race cars or rockets.

Formula One cars utilise carbon composites to retain rigidity while reducing weight. | Credit: Scuderia Ferrari

The main hurdle for using these carbon composite materials is the cost and complexity of manufacturing. Rocket Lab has overcome this hurdle by utilising a robotic manufacturing process that, while initially costly to implement, reduced the overall labour and time typically associated with such materials.

Dubbed “Rosie” (in homage to The Jetsons character), the robot is capable of making the carbon structures needed, and can also handle cutting, drilling and sanding. Overall, this reduces the overall manpower needed in production, as well as save time, as the robot can accomplish the same tasks much more quickly than a team of engineers.

Peter Beck, Rocket Lab founder, with “Rosie”. | Credit: Rocket Lab

Carbon composites aren’t the only innovation that the Electron rocket features.

Just Change the Batteries

Electrons main engine, the Rutherford engine, is particularly unique amongst orbital class launch vehicles. More specifically, it is the first, and most successful rocket to run on batteries.

Now, these aren’t AA batteries we’re talking about, but the overall principle remains the same. Those of you who are familiar with rocket engine cycles (or read my article on them) will know that typically, a rocket engine will use a smaller chemical reaction to power the engine’s turbopumps. The Rutherford engine instead opted for a battery powered turbopump assembly.

The main benefit of this approach is that the overall design is much simpler, as the battery powered turbopumps are undoubtedly easier to manufacture, especially considering the Rutherford engine is largely 3D printed.

Batteries do present some drawbacks that the Electron has factored into its design. The weight of the batteries needed to power such machinery is quite high. Electron’s aforementioned carbon composite body helps to mitigate this weight gain, but the Electron also jettisons any depleted batteries during the flight. This has been dubbed “hot swapping”, and is also useful in shedding the mass of the batteries once they have exhausted their usefulness.

The Rutherford engine. | Credit: Rocket Lab

While on the topic of rocket engines, the Electron also features an optional “kick stage”, which can give a little extra thrust to a satellite if it needs some additional manoeuvring. The Curie engine that is used on this kick stage is a pressure-fed engine which, rather interestingly, utilises a secret bi-propellant fuel combination. Rocket Lab may have stumbled upon something rather useful, it would seem!

The Curie engine has also once sported its own battery powered pumps, for NASA’s CAPSTONE mission. This indicates that Rocket Lab has developed at least two versions of the Curie engine, designed for different in-space applications.

Recycling?

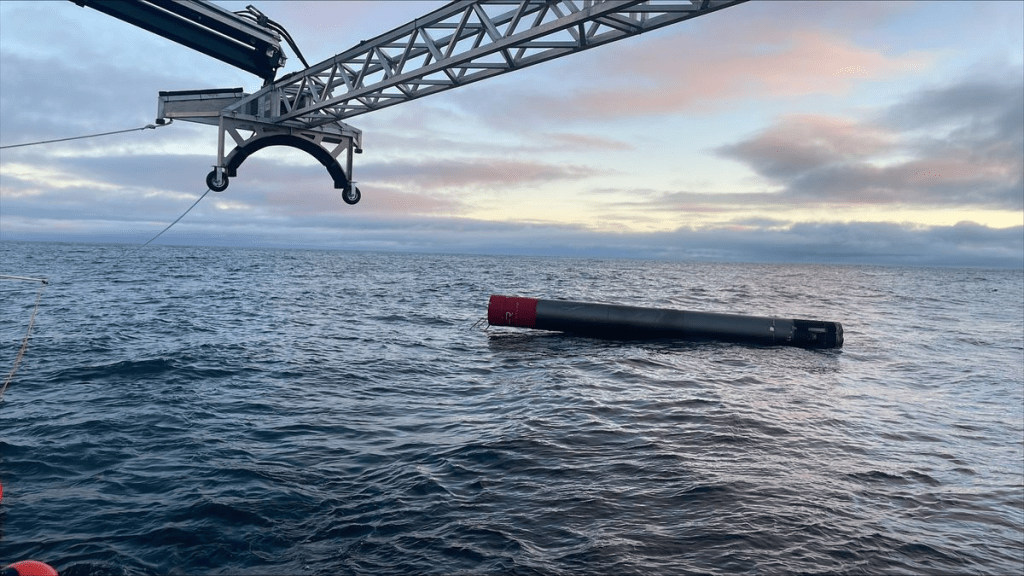

The Electron has also been the subject of various reusability experiments. Initially there were no plans to make the Electron reusable, but several modifications have since been made to a handful of boosters in order to ascertain the viability of splashdown refurbishment.

While Rocket Lab have, as of the time of writing, not yet reused an entire first stage, they have re-flown a Rutherford engine that, according to Peter Beck, was “perfect” in its performance.

Finally, the current idea to recover after splashdown comes after an attempt to catch the first stage with a helicopter. This idea was abandoned after a catch attempt demonstrated the difficulty of handling a helicopter under such unpredictable loads.

An Electron booster being recovered after splashdown. | Credit: Rocket Lab

Consistency is Key

The Electron, since its first launches, has demonstrated a remarkable consistency that has enabled it to complete 62 of 66 overall missions as of June 30th 2025. Quite a remarkable achievement for any launch company.

Rocket Lab has been responsible for launching a number of important payloads for various customers. Examples include climate monitoring satellites, maritime navigation satellites, Earth mapping satellites and NASA’s CAPTSTONE lunar CubeSat mission.

One last thing I’d like to bring attention to are the Electron mission names, which are typically some sort of fun play on words. Some of my favourites include:

- “Another One Leaves The Crust”

- “Ice AIS Baby”

- “Finding Hot Wildfires Near You”

- “Pics Or It Didn’t Happen”

- “That’s a Funny Looking Cactus”

Good fun.

See you next week!

Leave a comment