The Space Shuttle’s RS-25 engines during launch. | Credit: NASA

“It’s not rocket science”

That ubiquitous phrase to describe something as “not difficult” or “uncomplicated”. The phrase gives actual rocket science the perception that it is of such great complexity that no layperson could possibly understand.

Yet I believe that some rocket science can be accessible and understood for the average person.

What happens inside a rocket engine, and what makes all these engines different from one-another? Such questions can partially be answered by the engine cycle, or how the engine flows fuel through itself to achieve the desired performance.

This is one of the most interesting areas of rocket engineering, and this article aims to outline different engine cycles in an accessible way. A lot of simplification will be going on here, but this is in service of helping a layperson understand these concepts.

Maybe rocket science won’t seem so daunting for you after all.

Spin me Right Round

Before we look at some full cycles, we need to understand the why.

Rocket engines deal with extreme environments. Burning the amount of fuel at the rate that a rocket engine does leads to immense pressure wanting to escape the combustion chamber of the engine.

By design, the rocket engine ejects this pressure in the form of exhaust from the nozzle of the engine. This is the bit we see when we watch launches. This pressure is ultimately a large part of what makes a rocket engine work in the first place.

A poorly designed rocket engine may lead to pressure escaping elsewhere, in places where it is far from helpful. If the pressure inside the plumbing is less than that in the combustion chamber, it will escape into these pipes and cause many, many issues.

The issues in question. | Credit: JAXA

As such, a rocket engine must maintain an equal or higher pressure inside the pipes compared to the inside the combustion chamber. To achieve this, engineers use turbopumps to move fuel at immense speed and volume, thus generating these high pressures.

Ultimately, driving turbopumps is what a rocket engine cycle is for. Many different solutions exist for such a task, and I aim to cover some of the ones that are most often talked about and seen in the spaceflight world.

Gas-generator Cycle/Open Cycle

Yes, its another article where I made diagrams.

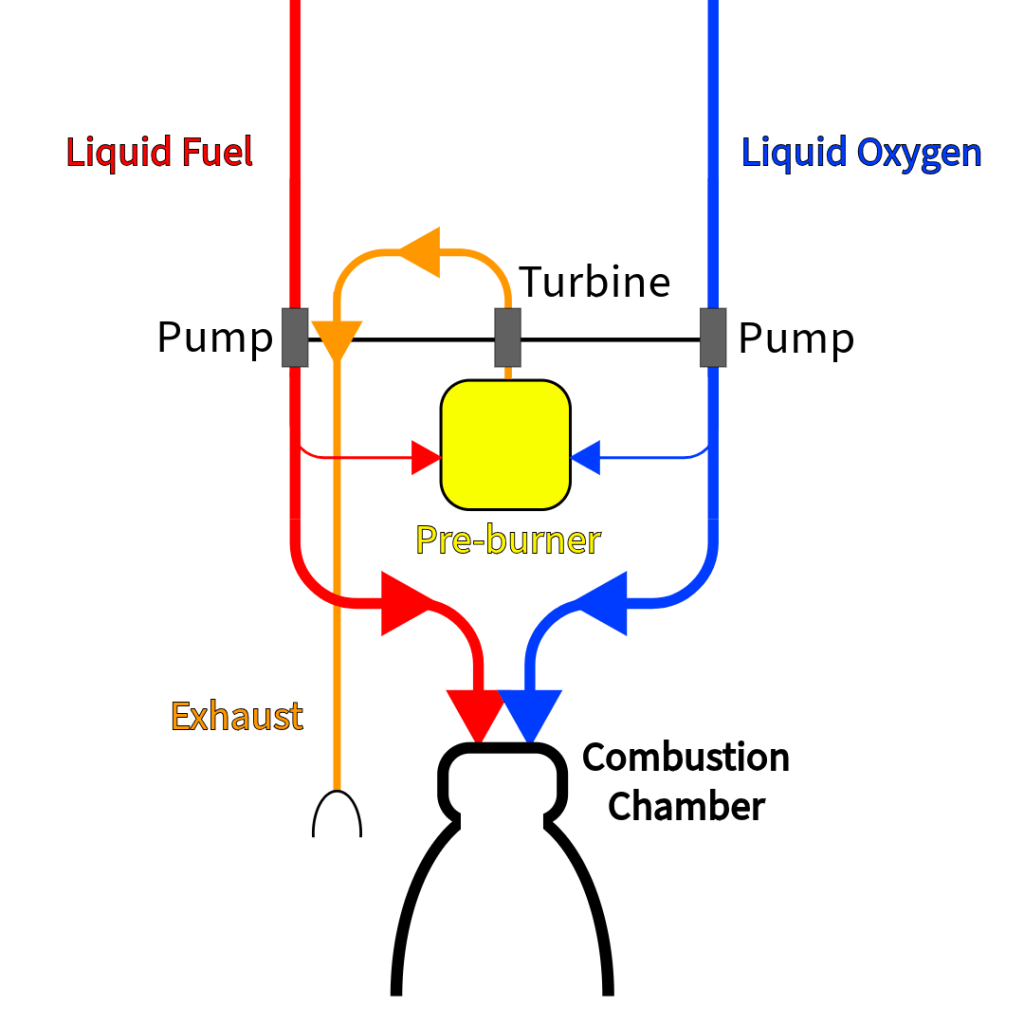

The gas-generator cycle (AKA open cycle) is a relatively simple type of cycle that I believe makes the perfect starting point for this discussion.

In the diagram, some basics can be observed. A rocket engine typically uses liquid fuel (such as methane or RP1) and liquid oxygen to achieve combustion.

Each fuel runs through a pump in order to achieve high levels of speed and volume on the way to the combustion chamber. As mentioned, this generates enough pressure to effectively feed the combustion chamber without pressure leaking back.

But how are the pumps powered?

The key to understanding this cycle, and the ones that come after, is the pre-burner section.

In the above diagram, a small amount of liquid fuel and liquid oxygen is fed into a chamber where they are burned. The exhaust from this smaller combustion is used to spin the central turbine, which is connected to the pumps in each fuel line.

If you ever used compressed air to spin a fidget spinner, you might understand this concept.

Exhaust from the leaf blower spins the fidget toy. A pre-burner in a rocket engine uses exhaust to spin a central turbine, which is connected to pumps. | Credit: Beyond the Press

To simplify and reiterate:

A small amount of fuel from each tank is burned to spin the turbine. This in turn powers the pumps of the rocket engine, allowing a large quantity of fuel to enter the combustion chamber at fast speeds.

In the above diagram, the gases used to spin the central turbine are ejected from the system in a separate exhaust. While this solution of dealing with pre-burned fuel is simple, it is less efficient than some of the more complex designs. As such, one of the key downsides of this approach is low relative efficiency.

Staged Combustion Cycles

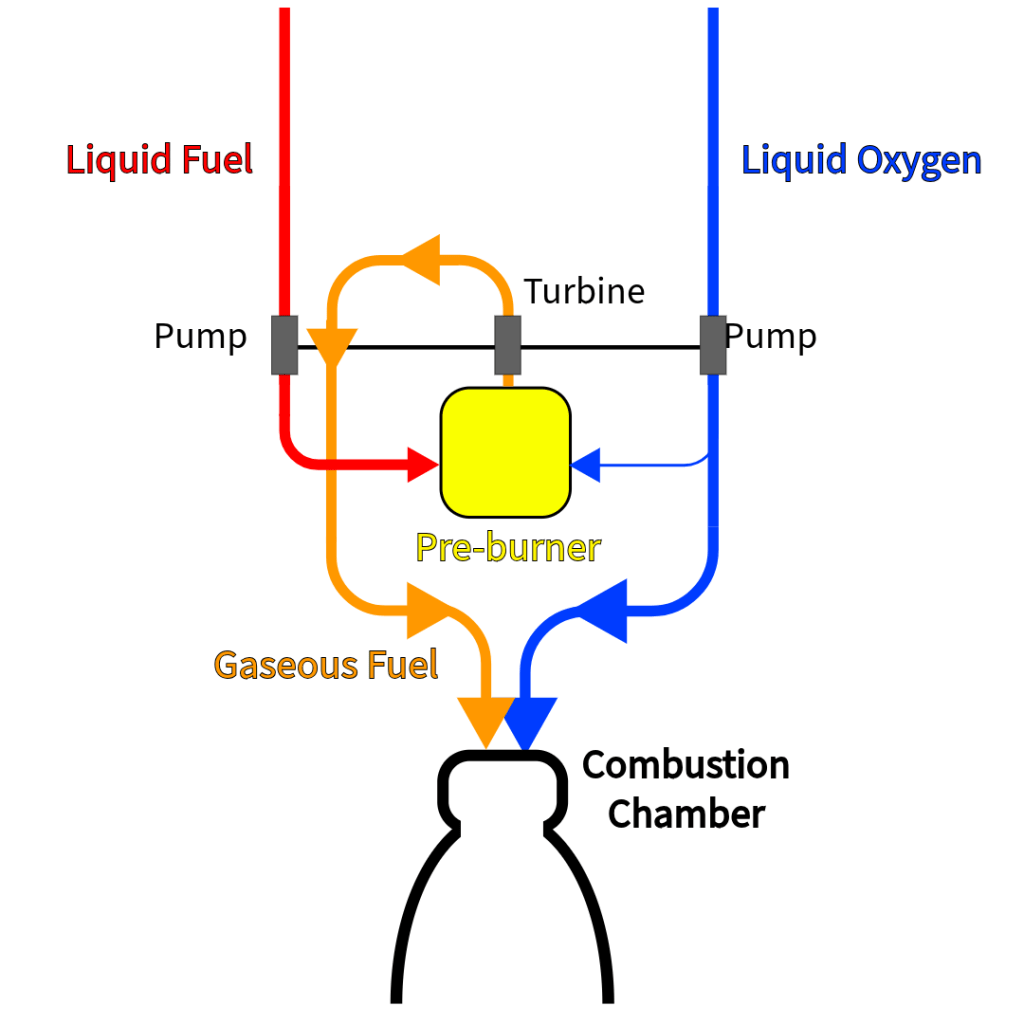

The staged combustion cycle can be seen as the logical next step for the rocket engine cycle. The key difference with this design is that the pre-burner exhaust gases are re-routed into the combustion chamber to be fully burned, instead of ejected overboard.

Liquid fuel is not fully combusted inside the pre-burner. A majority of the fuel simply changes state from liquid to gas instead of reacting with the little oxygen provided. As such, all of the fuel is routed through this system in order to reduce complexity.

The main benefit is self-evident in the fact that the fuel used in the pre-burner stage is not “wasted” by being ejected. Instead, it can be fully utilised by reacting with the rest of the oxygen inside the combustion chamber. This increases the overall efficiency of the engine when compared to the gas-generator cycle.

With regard to drawbacks, this approach increases the complexity of the design, meaning that more can go wrong in the process. Additionally, pre-burning certain fuels can create some other problems such as soot build-up inside the engine. Soot blocks the pipes, creating bottlenecks where fuel flows less efficiently, and may cause pressure build-ups that the engine is not designed to handle.

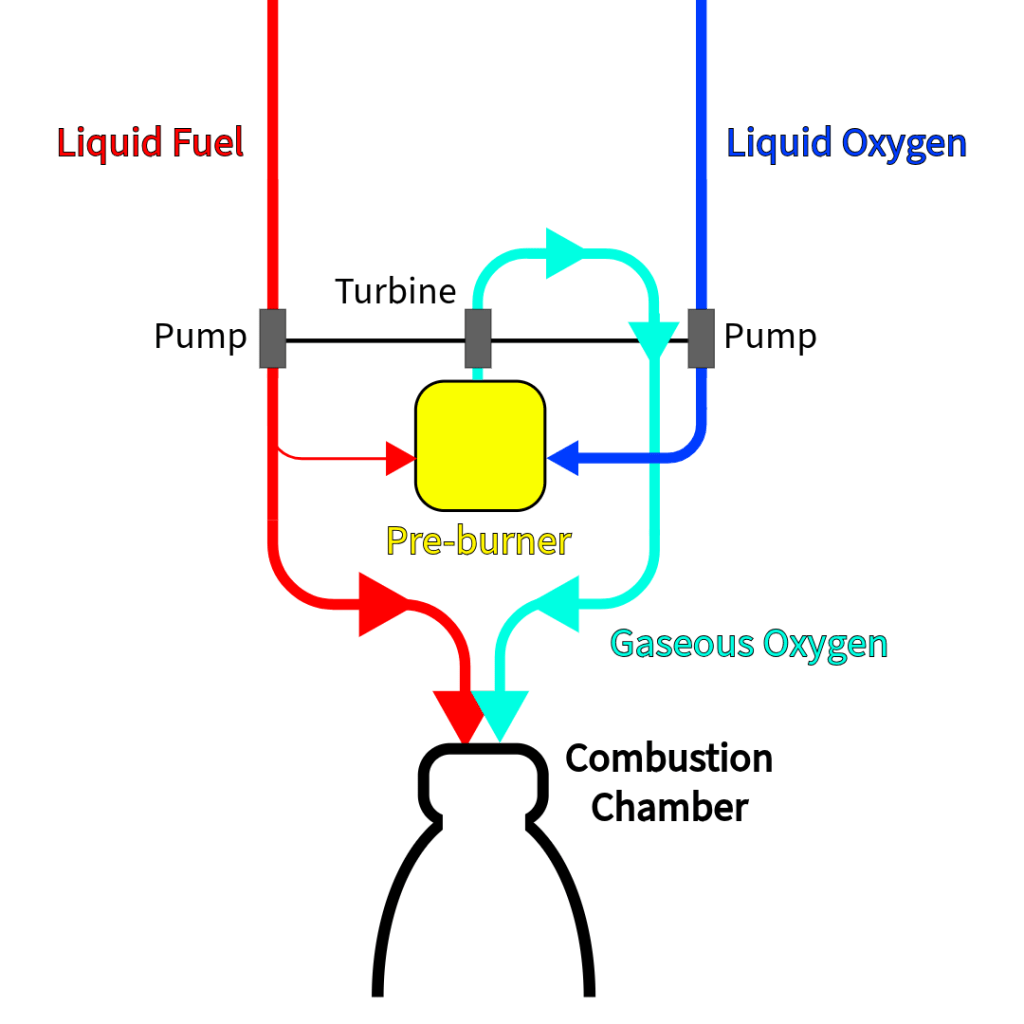

One solution to the soot problem may be to reverse the roles of the fuel and oxidiser inside the pre-burner, like so:

By using oxygen as the primary reactant inside the pre-burner, the soot problem can be avoided entirely. Gaseous oxygen, however, is extremely reactive, and this solution creates new problems in the form of erosion inside the pipes of the rocket engine. Specialised metal alloys are implemented inside this type of staged combustion cycle to avoid such erosion, which can be a costly endeavour.

The primary fuel used inside the pre-burner for each of these cycles denominates the specific type of staged cycle it is (fuel-rich staged combustion or oxygen-rich staged combustion). They work under the same principle, but by using either the fuel or oxygen as the primary pre-burner reactant, different benefits and drawbacks can be exploited or mitigated.

Using fuels that do not produce soot after pre-burning is another way to mitigate the problem, which is where another form of the staged combustion cycle comes in:

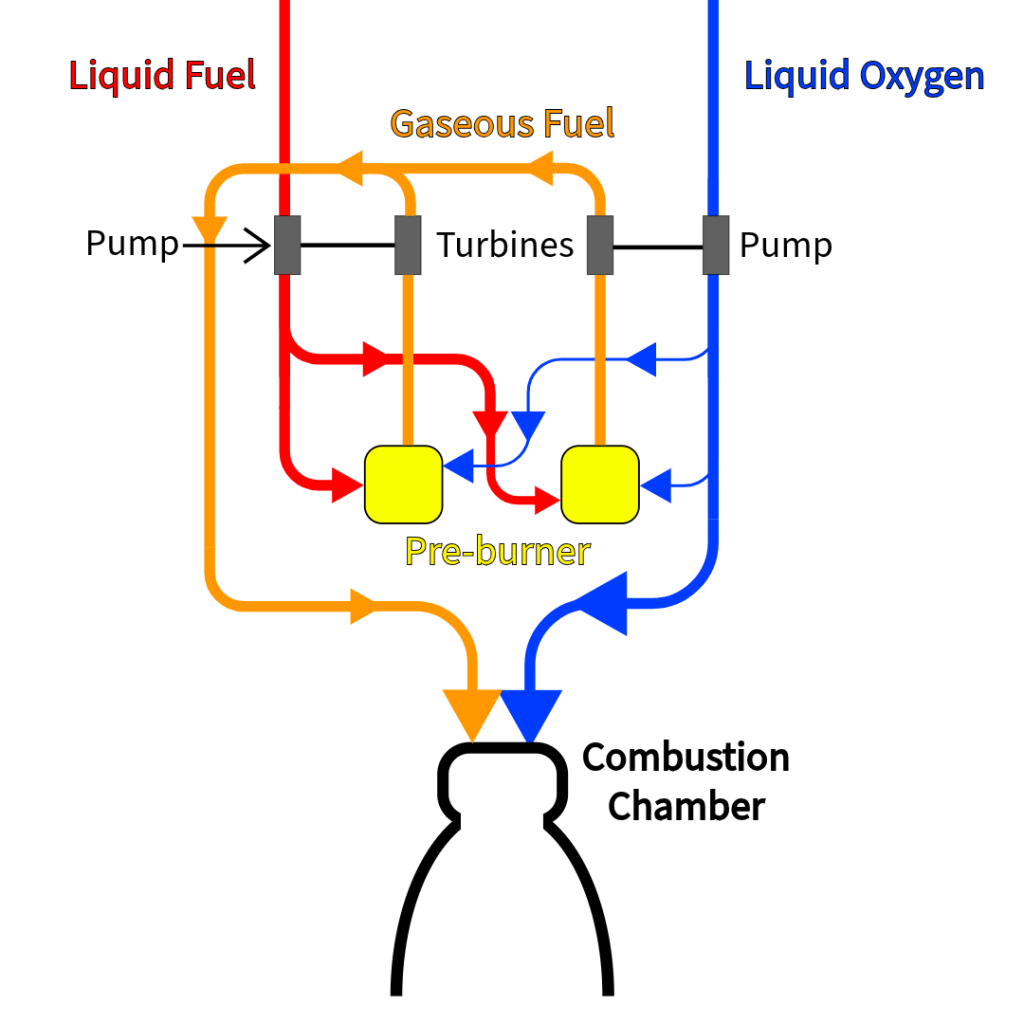

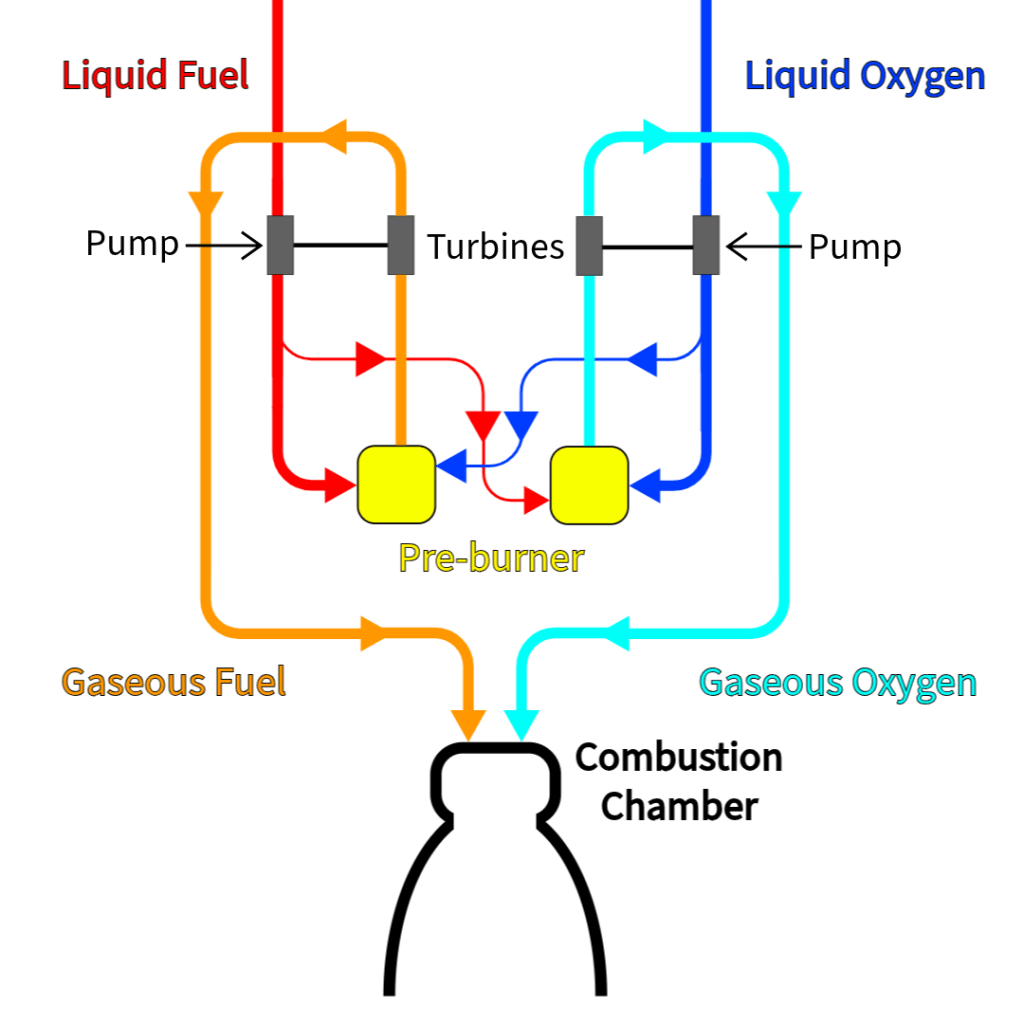

This is the magnificent fuel-rich dual-shaft staged combustion cycle.

Bit of a mouthful.

As made famous by the Space Shuttle’s RS-25 rocket engine, this form of the fuel-rich staged combustion cycle avoids using soot-producing fuels in favour of liquid hydrogen. This allowed the engineers to create an efficient engine that does not suffer from the downsides of soot build-up or the need for expensive metal alloys.

Added complexity, however, was necessary for this design to work. As liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen have vastly different densities, one single turbine connected to both pumps would not be sufficient; it would have to spin at one speed that favours a better flow rate for either the hydrogen or oxygen. To overcome this, engineers created two separate fuel-rich pre-burners that span independent turbines at different speeds, so that both fuels could have an optimised flow rate through the engine. This is shown in the diagram above.

A master-work of engineering by humanity.

There is one final downside to the staged combustion cycle family of engines that I have neglected to mention thus far.

Each of these engines, while more efficient than the gas-generator cycle, loses some efficiency in the combustion chamber itself. As one of the fuels enters as a liquid, and the other as a gas, efficiency is lost. Typically, gases react more effectively than liquids, as the molecules are more free to move about and are thus more likely to collide than in a liquid reaction. As only one of the fuels is in gaseous form, achieving a highly efficient combustion is difficult.

Our final engine cycle aims to iron out this key downside:

Full-flow Staged Combustion Cycle

This is the full-flow staged combustion cycle, arguably the most efficient rocket engine that humans can currently create.

Much like how the staged combustion cycle is an evolution of the gas-generator cycle, the full-flow staged combustion cycle is an evolution on the standard staged combustion cycle.

As alluded to earlier, the goal of this engine is to have both fuel and oxidiser reach the combustion chamber in gaseous form, increasing the combustion efficiency and thus overall efficiency of the engine.

In order to achieve this, two pre-burners are utilised, one of which is fuel-rich and the other oxidiser-rich. As a result, both fuel and oxidiser enter the combustion chamber in gaseous form, thus increasing their reactivity with one another.

The full-flow staged combustion cycle really is a test of our current technology. So far, SpaceX’s Raptor engine is the only engine of this type to have flown. Challenges native to more “traditional” staged combustion cycles (such as erosive gaseous oxygen) must be overcome alongside the added complexity that is necessary for a full-flow staged combustion cycle to work. Overall, it is a marvel that any of these engines have been built and flown at all.

Breathe…

The reader right now…

I know this article has been one of those more technical ones, but I really find these engine cycles interesting and I hope I communicated to you how they work and why they are the way they are.

There’s lots of other engine cycles that weren’t discussed here, that might be worth a follow up. Let me know if that interests you!

See you next week!

Leave a comment