Gemini 6 spacecraft as seen by Gemini 7. | Credit: NASA

My Revelation

I’ve had a great time doing this blog, and one of the many joys it brings me are the questions from friends and family regarding the subject matter of my articles. I appreciate that the general public has little to no knowledge about the science of space travel; by writing these pieces I hope to bring the topic to an audience who may have otherwise considered it beyond their understanding.

With this objective in the back of my mind, I recently realised just how difficult it is to explain some of the strange and counter-intuitive concepts of orbital mechanics to a layperson. I’ve given it much thought the past few weeks, with this article finally coming to fruition after a conversation I had with my girlfriend regarding some common spaceflight misconceptions.

I’m therefore extremely excited to present to you the one and only teaching tool you’ll need to understand how spacecraft move in orbit:

Credit: Swingball

Tetherball, Totem Tennis, Swingball. All valid names for this childhood pastime. Even I, renowned for not being the outdoorsy type, used this as a kid. Sure, all I remember is being hit in the face multiple times over by the damn thing, but still.

I’ve come to realise that tetherball actually presents a brilliant analogy for orbital mechanics. You can think of the pole as the Earth, the string as gravity, the ball as a spacecraft and the bat as the rocket engine. A top down perspective on the whole setup is the final thing we need to make this work and we’re off to the races!

The Basics

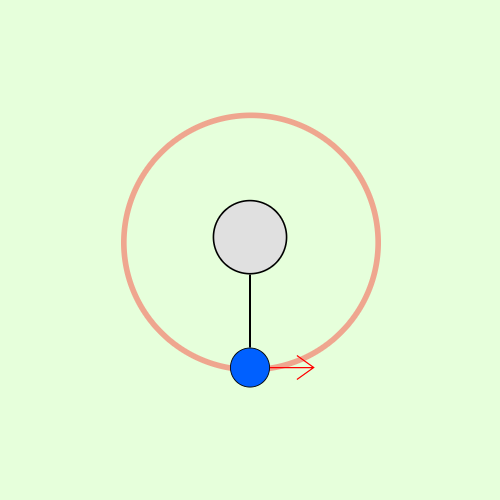

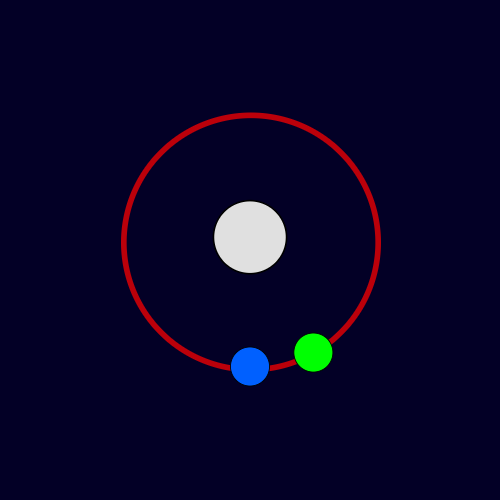

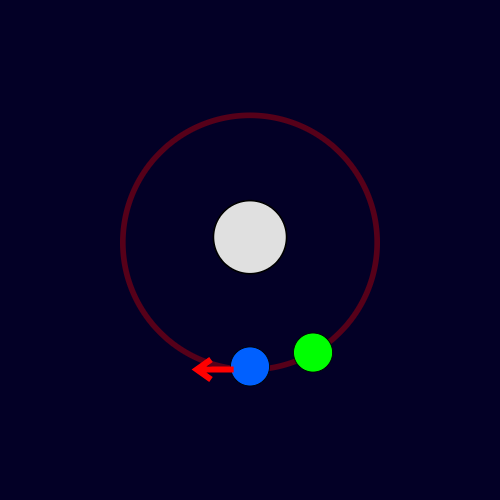

Lets start our tetherball tutorial off with a basic orbit:

In my wonderful diagram, you can see the pole in the middle, the tennis ball and the string attaching the two. I have also shown the trajectory of the tennis ball with the red curved line, and the arrow represents the direction you hit the ball to keep it going.

(Note: In space, a spacecraft does not need to keep firing its engines every orbit to stay in space. This is just a limitation of the analogy.)

From the above diagram (and as you probably know from experience) it is clear that when we hit the ball, it orbits around the pole. This is how spacecraft stay above Earth for extended periods of time. By achieving enough speed, the spacecraft can “miss” Earth when it falls, thereby achieving an orbit.

Its like throwing a ball so hard that it goes around the world and comes back to you. That would be a good party trick!

Changing Altitude

With this analogy we can now pose some questions, such as what if we hit the ball harder?

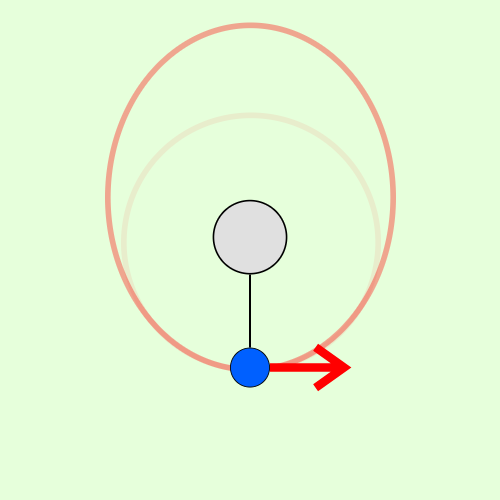

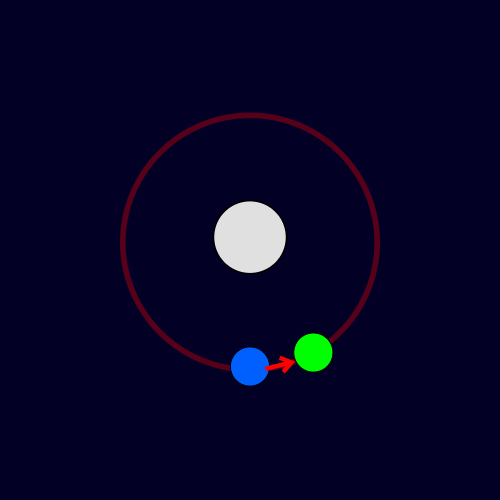

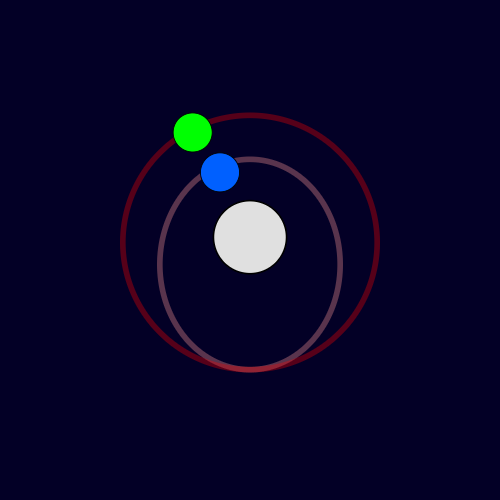

In this diagram, the bigger arrow represents us hitting the tetherball with more force. As you can see, the trajectory of the ball changes because of our senseless aggression.

The new trajectory brings the ball further out from the pole on the end opposite from which we hit it. Typically this ends with someone, probably a friend or sibling, being hit square in the face. For clarification, the previous trajectory is also visible so that the difference is easily observed.

In real life, this is how a spacecraft can change the altitude of its orbit. By firing its engines in the direction of its travel (called prograde), it can increase its speed at that point and therefore “fling” itself further away from Earth on the opposite end.

Once our tetherball reaches the furthest point from the pole (called apogee), centripetal force becomes dominant. As a result, the ball curves back towards the batter and ends up back where it was originally hit.

Our spacecraft too will follow this trajectory. As the spacecraft makes its way further from Earth, it loses the speed gained by the engines firing due to the pull of gravity. Eventually, at apogee, this loss of speed is great enough for the spacecraft to start falling back to Earth.

Unlike our tetherball however, the spacecraft does not experience air resistance or the friction of the string rubbing against the pole, and so it regains this speed as gravity accelerates it. As such, the spacecraft eventually regains all the speed lost on the ascent and once again “flings” itself out, following the same trajectory as before.

If we want our tetherball to maintain the further distance from the pole, we just need to repeat the same motion at apogee. This means apologising to the person that you hit with the ball…

With the power of friendship, the second person can hit the ball at its apogee, thus circularising the balls orbit further away from the pole. Well done both of you.

In orbit, this is how a spacecraft can increase its overall orbital altitude above Earth. This two step manoeuvre is called a “Hohmann Transfer”, for those curious.

If we want to decrease our orbital altitude, it is simply a matter of doing the reverse.

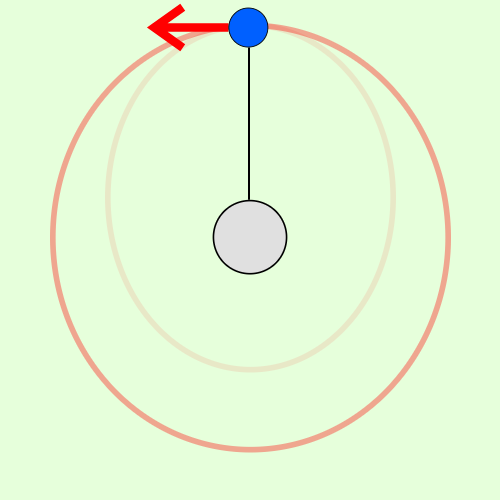

With this analogy, imagine that you gently brush the tetherball as it passes you. This will impart a force (friction) in the opposite direction of the balls motion, as represented by the red arrow. It is important to remember that the ball is still going anti-clockwise, it just lost some speed.

As a result of the loss of speed, the ball falls towards the pole as it does not have sufficient momentum to continue orbiting on its previous path. The lowest point it reaches is called perigee.

In orbit, a spacecraft would fire its engines in the direction opposite to its direction of travel (called retrograde), decreasing its speed at that point and thus falling further towards Earth.

As with the previous example, the spacecraft will eventually gain the speed back due to gravitational acceleration, and will return to the point at which the engines were initially fired.

If the spacecraft dips into the atmosphere, drag will slow it down sufficiently that it cannot continue its orbit. I actually have an article talking about this already!

Slow is Fast? Fast is Slow?

I mentioned at the start of the article that there’s some counter-intuitive thinking involved in orbital mechanics, and with these basics out the way we can look at how trying to move towards an object in orbit actually makes you move further away.

We can do away with the tetherball analogy now. It served us well, but you’ve all graduated to a slightly different variety of diagram!

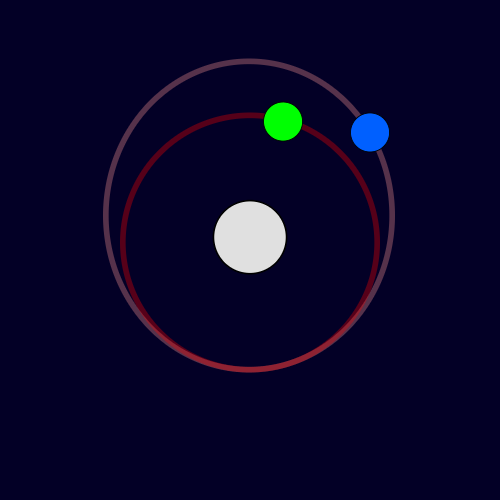

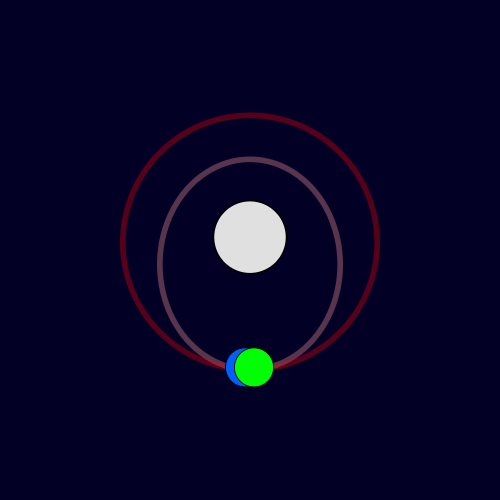

In our diagram, we can see two orbiting spacecraft. They share the same orbit as represented by the red line. The blue spacecraft is following the green spacecraft going counter-clockwise, and they’d like to meet up at the same point so they can exchange pleasantries.

Now, you might think to do this:

Just fire the engines so that we go towards the green spacecraft, right?

Unfortunately, this will only increase the distance between them. Remember what happens when we burn our engines in the direction of our travel?

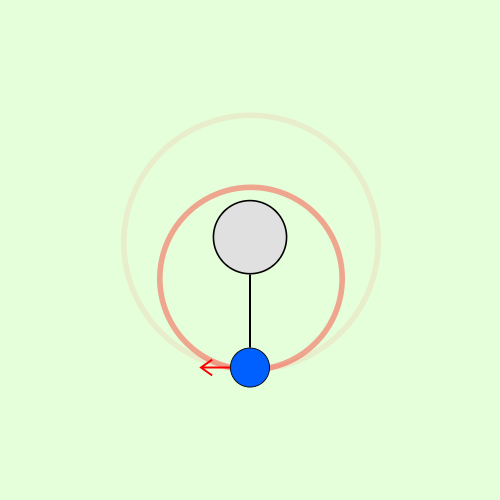

Now the blue spacecraft has increased its apogee, and the speed it gained initially by firing its engines has been lost from the pull of gravity. Due to the higher apogee, it is taking a longer path than the green spacecraft. As such, when it comes around to complete its orbit, it ends up further away from the green spacecraft:

Oh dear.

When we decided to fire our engines towards our target, as our intuition might tell us to do, we did not account for our overall orbital motion. We did not account for the fact that it will increase our apogee (making us travel a longer path), and the effect that gravity will have on our spacecraft once we finish the engine burn.

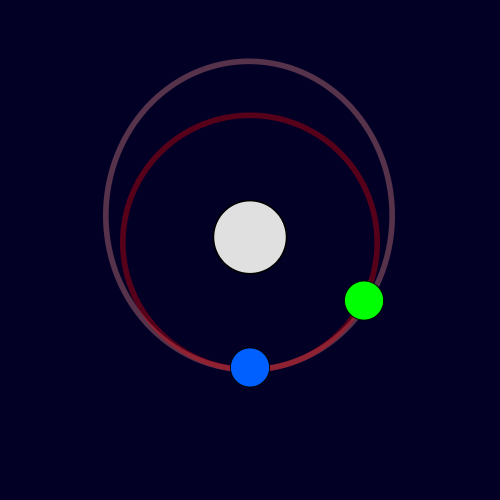

If we can throw our intuition away for a moment, we can figure out the solution:

Fire our engines away from the target! Completely obvious I’m sure you’ll all definitely agree.

Let’s review what happens when we do this:

The blue spacecraft has now decreased its perigee, thus reducing the distance it has to travel to complete one orbit. Additionally, it makes up for the initial speed lost when firing retrograde, utilising gravity’s pull to accelerate it towards its lowest point.

Now they’ve met! Pleasantries have well and truly been exchanged.

The blue spacecraft just needs to raise its perigee back up to match the orbit of the green spacecraft. By now, you hopefully understand the two manoeuvres that I discussed here, so I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader…

A Brain Teaser

If you’re really into all this, I invite you to also consider what other directions a spacecraft could fire its engines, and what effects this would have on its orbital trajectory. I may consider a part two where I can explain other manoeuvres in a similar fashion. If I get good feedback, I’ll definitely do it!

I hope you learned something about how spacecraft move in orbit.

See you next week!

Leave a comment