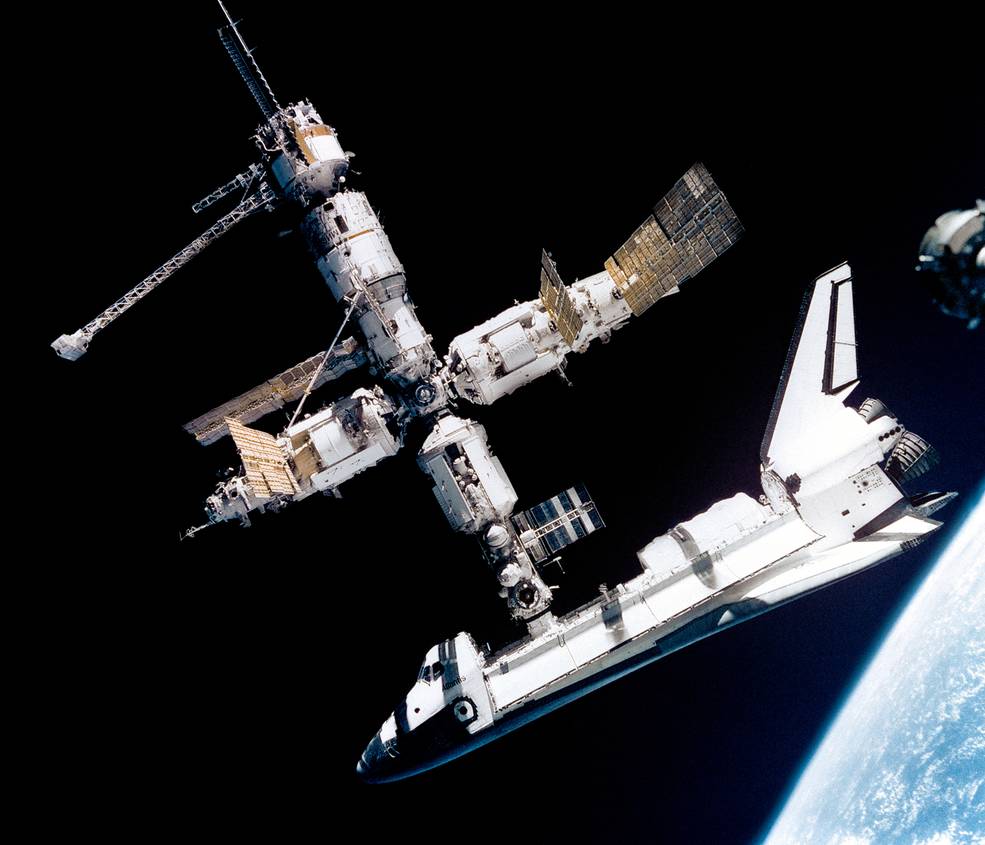

Space Shuttle Atlantis docked with the Mir space station. | Credit: NASA

Here’s a fun fact. If you were born after November 2nd 2000, your entire life has been lived while there are people in space. I just miss this date myself, being a June baby. I’m such a dinosaur…

For over 20 years now humans have been occupying space in some capacity non-stop. This kind of record would not be possible without the development of the International Space Station (ISS), the hottest destination in low Earth orbit.

Providing us with scientific research since its life began, the ISS is a result of decades of space travel development and experience, and would not have been possible without the contributions made by the programs that came before it.

What kinds of space settlements were there before the ISS, and what did we learn from them?

Spying and Salyut

Unsurprisingly, this space history takes us back to the Cold War.

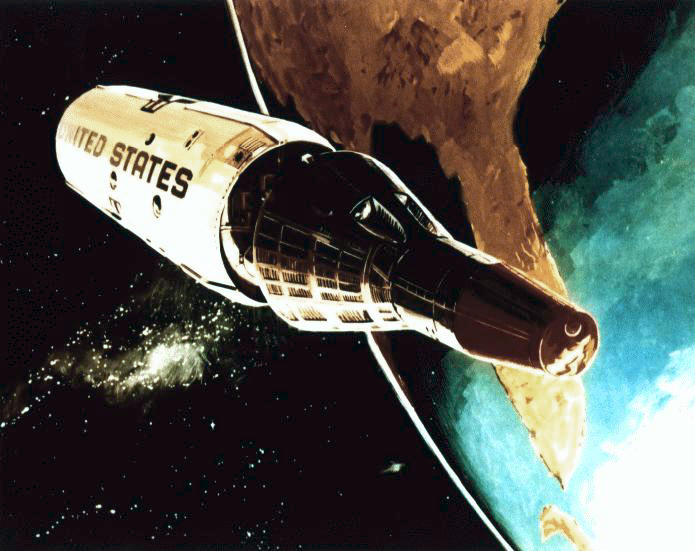

The desire for longer term space habitation can be traced back to the 1960s, when the United States Air Force (USAF) greenlit the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL), a single use space station that would be used for real-time military reconnaissance.

Spy satellites at the time would deploy film canisters back to Earth, and they would have to be retrieved manually. Sending images back to Earth digitally was practically non-existent at the time, and so the best way to get high quality images back was the aforementioned method.

The USAF wanted a way for time-sensitive imagery to be retrieved on-demand, as recovering and developing the film from the satellites already in operation took up to several days, by which time the information could be, and often was, outdated.

As a result of this perceived need, the USAF reasoned that having a manned space station would accomplish the desired result of fast, up to date reconnaissance. Having astronauts on-board meant that observations could be made and relayed back to Earth via communication links as and when they were needed, rather than waiting days to recover, develop and analyse photographs from orbit. Additionally, the USAF believed that astronauts could make judgement calls about which sites to observe, and make decisions on-orbit that would not be possible with a satellite, which needed to be directed in advance.

Ultimately the MOL program would be cancelled in June 1969 with no crewed flights taking place. Competing costs with the Vietnam war, and improvements in automated spy satellites made the system ultimately undesirable to the US government, and it was shelved.

Concept Art of the MOL. | Credit: USAF

While the MOL concept was eventually cancelled, the idea of a military reconnaissance space station caught the attention of the Soviet Union, and this time, it would fly.

As with the MOL, the Almaz military space station had its roots in the 1960s. Vladimir Chelomey, a Soviet engineer, promoted the idea as a response to the MOL program, which was widely publicised in the US.

During the development of Almaz, it was realised that a civilian version of this station would provide the Soviet Union with a useful cover story for their launches, and generate some much needed prestige for the country after the Americans won the race to the Moon. Designated Salyut, the first of these stations went from conception to launch in just 16 months.

As a result, on April 19, 1971 Salyut 1 became the world’s first space station.

Technical Difficulties

Salyut 1 as seen by the fated crew of Soyuz 11. | Credit: Viktor Patsayev

The Salyut program wasn’t without its problems. In fact, early space stations were plagued with technical issues.

Salyut 1 was initially planned to home the crew of Soyuz 10. The Soyuz spacecraft was the Soviet’s successor to the Voskhod, and was originally developed as the crewed spacecraft to take cosmonauts to the moon. Its new assignment was to ferry cosmonauts to and from Salyut.

The crew of Soyuz 10 would not find this task so easy. Upon reaching the space station in April 1971, they found that the docking mechanism was faulty. While their Soyuz could perform a “soft-capture”, their spacecraft would not close all the latches to complete a full “hard-docking”. As such, the cosmonauts could not enter the space station safely and had to return home early.

Salyut 1 would only face more difficulties, and unfortunately the crew of Soyuz 11 would meet an untimely death during their mission to the station. After replacing a ventilation system to clear a smoky atmosphere inside the station, and extinguishing a fire on the 11th day of their mission, you would be forgiven for thinking the crew would be happy to leave Salyut.

On 29th June 1971, after undocking and firing their engines to return home, the Soyuz spacecraft jettisoned the orbital module and service module as part of the re-entry preparation. All the automated systems brought the capsule back to Earth, seemingly without a hitch.

When recovery teams opened the capsule back on Earth, they found the crew asphyxiated. Kerim Kerimov, chair of the State Commission, recalled that:

“On opening the hatch, they found all three men in their couches, motionless, with dark-blue patches on their faces and trails of blood from their noses and ears. They removed them from the descent module. Dobrovolsky was still warm. The doctors gave artificial respiration. Based on their reports, the cause of death was suffocation.”

Soyuz 11 crew. | Credit: NASA

While not a fault with Salyut itself, this tragedy, combined with all the other difficulties faced by the station, was enough to have it decommissioned. Salyut 2 was launched in 1973. What else could possibly go wrong?

Salyut 2 depressurized and lost control within two weeks of its launch. No crews visited.

Somehow, despite all these setbacks, the Salyut stations kept going. In fact, Salyut 3 was home to the first weapon fired in space (a 23mm cannon, for those curious).

Salyut 6 would be the first truly successful Salyut station. Launched in 1977, Salyut 6 would be the first of the Soviets “second generation” space stations, marking a significant technological jump from the stations before it. 683 of its 1764 days in space were spent occupied. 16 cosmonauts eventually visited the station over its almost 5 year flight.

The final Salyut station, Salyut 7, would prove that Russia had what it takes for long term space habitation. Occupied for 816 days, Salyut 7 is best known for a daring recovery mission after the station lost power and began to drift in February 1985.

In what author David Portree describes as “one of the most impressive feats of in-space repairs in history”, the crew of Soyuz T-13 docked with the “dead” station, donned winter clothing to protect themselves from the freezing air, and set about successfully repairing the station.

Saving Skylab

The Russians weren’t the only ones struggling to deploy a successful space station. On May 14th 1973, the American’s first space station, Skylab, was launched. Just like Salyut, Skylab suffered a number of technical hitches.

Skylab, launched atop a Saturn V rocket. | Credit: NASA

Two main problems plagued the station upon reaching orbit. First of these issues was the micrometeorite shielding coming loose. Designed to protect against micrometeorite strikes, and also regulate the temperature of the station, without the shielding the station would not be safe to inhabit for long periods of time.

Adding to these woes was the electrical power generation, or lack thereof. One of Skylab’s solar panels failed to deploy, due to debris from the aforementioned micrometeorite shield damage.

The other solar panel just came off.

As with the Salyut stations, it would come down to the bravery and ingenuity of humans to solve these issues. On a mission designated Skylab II, a crew of 3 astronauts, including moon walker Pete Conrad, went about repairing the damage sustained during the launch.

NASA thankfully had Jack Kinzler, lovingly dubbed “Mr. Fix It”, on the case. Kinzler designed a parasol that could be deployed from within Skylab, which would replace the missing micrometeorite shielding and help to regulate temperatures inside the station.

Skylab in orbit. A missing solar panel array and the parasol are easily visible. | Credit: NASA

Mr. Fix It had the right idea, and the parasol was successfully deployed, regulating the temperature inside the station, and allowing the crew to turn their attention to the stuck solar panel.

Astronauts Conrad and Kerwin performed a spacewalk to attempt to pry free the stuck solar panel. Using a big pair of cable cutters, jammed debris was eventually cut loose from the panel, and the solar array deployed. In fact, the deployment was violent enough to throw both astronauts from the hull of Skylab, with the strength of their tethers being tested.

Skylab would eventually go on to perform many different scientific experiments, and was occupied for 171 days of its life.

How Clean is Your Space Station?

With all the learnings and successes from the Salyut programme, the Russians moved onto their next ambition.

Mir was the world’s first modular space station. Between 1986 and 1996, many different modules were launched and docked to Mir in order to expand living space and provide different scientific capabilities to the station.

Mir set a number of records during its tenure. Up until 2010, Mir held the record for the longest human presence in space at 3,644 days. Valeri Polyakov also set a spaceflight record that is still held as of February 2025, with the longest single human spaceflight at 437 days in space.

While clearly a major technological breakthrough in space habitation, Mir still had its fair share of quirks.

As a neat freak, living on board Mir in its later years sounds like a bit of a nightmare to me. After 10 years of operation, so much stuff had accrued in the older parts of the station that it was extremely cramped. Astronaut John Blaha reported that the station “looked used.”

An understatement, in my opinion.

Mir’s core docking node, showing the claustrophobic nature of the older modules. | Credit: NASA

Hoarding is considered a fire hazard, and rather unsurprisingly at this point, a fire broke out on Mir in 1997. An Oxygen generation system dubbed Vika malfunctioned and set on fire. Thankfully, the crew were able to subdue the blaze after 3 fire extinguishers were used in an attempt to avert danger.

As a result of the fire, toxic smoke lingered in the station for 45 minutes, meaning that the crew had to wear respirator masks. It’s worth mentioning at this point that some of the fire extinguishers were immovable (likely due to clutter), and some of the respirator masks were broken.

Astronaut Jerry Linenger wearing a respirator following the Mir fire. | Credit: NASA

Kim Woodburn and Aggie MacKenzie would have an absolute meltdown aboard Mir, and that’s not just because of all the hoarding. Delightfully, there was also a variety of microorganisms growing in the walls of the station, which produced a pungent smell.

Oh, there was also mould.

Bacteria growing in my walls sounds like some sort of dystopian horror story, but such was life aboard Mir. By the time the station was decommissioned in 2001, 140 different species of microorganisms were identified on board. Thankfully this experience resulted in many learnings for the ISS, as any bacterial strains are now carefully monitored to ensure a healthy and clean living environment for crew members.

Finally on the list of major Mir incidents we have the crash.

During a resupply mission, the Progress M-34 spacecraft was slated to test a new manual docking system. Previously, the Progress spacecraft had used the Russian Kurs docking system, which was expensive, but is extremely reliable and is still in use today.

TORU was the manual docking system to be tested, and was controlled by a crew member on board Mir. Think of it as a remote controlled spacecraft. I’d love to try that myself…

During the test on Progress M-34, an equipment malfunction caused Progress to become inoperable, just as it was heading straight for the station. The spacecraft slammed into the Spektr module of Mir, puncturing the hull and damaging solar panels. Spektr was permanently sealed off as a result of this damage, as it was considered damaged beyond repair.

Solar panel damage also caused a power problem as the damaged panels were supplying a large quantity of the stations power. Mir would experience power downs and drifting due to the extensive damage; weeks of work was necessary to bring the station back up to regular operation.

Damage caused by the collision with Progress M-34. | Credit: NASA

Modern Living

Nowadays we don’t hear much about the ISS and what goes on up there in mainstream news. Any incidents are small enough to not make headlines, and that just shows how much has been learned from all the history discussed thus far.

That’s not to say life on the ISS is without incident. Some may remember that in 2018 an air leak occurred in the ISS due to a 2mm hole present in the Soyuz MS-09 spacecraft. Media outlets picked up on this and there was a brief space themed “whodunnit” regarding the origin of the hole. Russian officials blamed Americans, others say it was just an accident. Some seem to think the hole was a revenge plot by someone after a failed romantic relationship with a crew member.

Out of this world stuff.

Cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko cuts into thermal blankets of the Soyuz orbital module to identify the source of the leak. | Credit: NASA

What matters in the end is that the leak was patched up, and no harm came of the incident. Indeed, this is how most problems end now on the ISS, and the crews are no doubt happier for it.

I hope you learned something about the dense and dangerous history of space stations.

See you next week!

Leave a comment